BROACH I BROOCH

CRAIG GALLERY, DARTMOUTH, NS

MAY 29 – JUNE 22, 2019

By: Lindsay MacDonald

Published: 2019/07/12

Broach I Brooch at Craig Gallery

The effort put forth by Co-Adorn, for their exhibition at Craig Gallery in Alderney Landing in Dartmouth, is a significant milestone for contemporary art jewellery in Nova Scotia. We are a scrappy field, commonly misunderstood, and often on the defensive. This Canadian survey reaffirms what we already knew, and what the public is coming to understand: that Canada has no shortage of jewellery artists who are eager to be heard and who are extremely competent.

Broach I Brooch

Presented at Craig Gallery in Dartmouth, NS, in a large window of undulating panels, the exhibition’s 44+ brooches are numbered and indexed objectively. Twenty years ago, such a public display of art jewellery, located near the Dartmouth ferry terminal, would have been unheard of. The decision to exhibit in a location populated with commuters shows wonderful insight by both Co-Adorn and Craig Gallery. Traditionally, Nova Scotia has valued those who work with their hands via the trades, fisheries, pulp and paper, ship building, and folk art. It stands to reason that the same appreciation would lend itself to the expertly rendered micro-worlds of jewellery. Art jewellery needs more visibility in Atlantic Canada. Makers have always been here; some self-taught and many channelling through the bright spots of NSCAD University and the New Brunswick College of Craft and Design. Now, we need wearers.

With this exhibition, Co-Adorn gently prods jewellery back on the body. To borrow from the statement of represented artist Peter Lawrence, “it has to be wearable if it is to be worn”. This quality of directness is present throughout Broach I Brooch. Co-Adorn chose the brooch as the focal point of the exhibition and gave simple requirements: it was mandatory for the piece to have some sort of fastening capabilities. This caveat encompasses the historical significance of society’s more functional fasteners, as well as the expressive, decorative, direct and often radical “pin”.

Louise Perrone

Aubergine Bisector

Fabric, plastic, thread (reclaimed), magnets

The tradition of the pin as a radical affirmation of “self” is nowhere more apparent than in the works of Louise Perrone and Lyndsay Rice. Louise taps into popular emoji culture with her eggplant brooch Aubergine Bisector. This adaptable object is overtly tongue-in-cheek, but softened with hand stitching and a tactile approach, making the piece simultaneously subversive and sensitive to what could simply be a private discourse between lovers. Lyndsay Rice powder coats badges of honour and combines them with plumage. Her dynamic use of scale lends an otherworldly context to her encoded emblems. The wearer is declaring something about their identity, but the message is obscured.

This re-contextualization of sign and symbol is also present in the pristine work of Anneke van Bommel. Her work in wood, silver, and nickel silver offers a poignant interpretation of the early 19th Century ritualist logic of Memento Mori. Anneke integrates the elemental materials with a confident and skilled hand. Anja Šućura and Emily Lewis reference the history of ornament as well. Šućura looks to the 18th Century tradition of the “lovers eye” brooch, rendering it in technicolour, while Lewis strips a Morris-inspired floral motif of its colour, replacing it with ethereal white and neon green. Her “boutonniere” trio glows with reference to an alternate past.

The presence of the region’s art schools is made very apparent by the work that dazzles with material mastery. NSCAD professor Rebecca Hannon’s brooch Doxie defies any mis-categorization of digital processes as being “simple” by building laser cut units into beautifully balanced wearable tessellations. The fact that her precious works are built from humble architectural offcuts asks us to re-evaluate what we view as valuable in this ever-changing world of objects. Anne-Sophie Vallée also uses industrial compounds, but applies an altogether different working logic to them. In order to free herself from her own agency as artist she acts more as a mediator between material and user. The result transforms the mundanity of building materials into compelling, almost cosmic wearable composites.

Anneke van Bommel

Oleander Corsage Brooch

Nickel silver, ebonized walnut

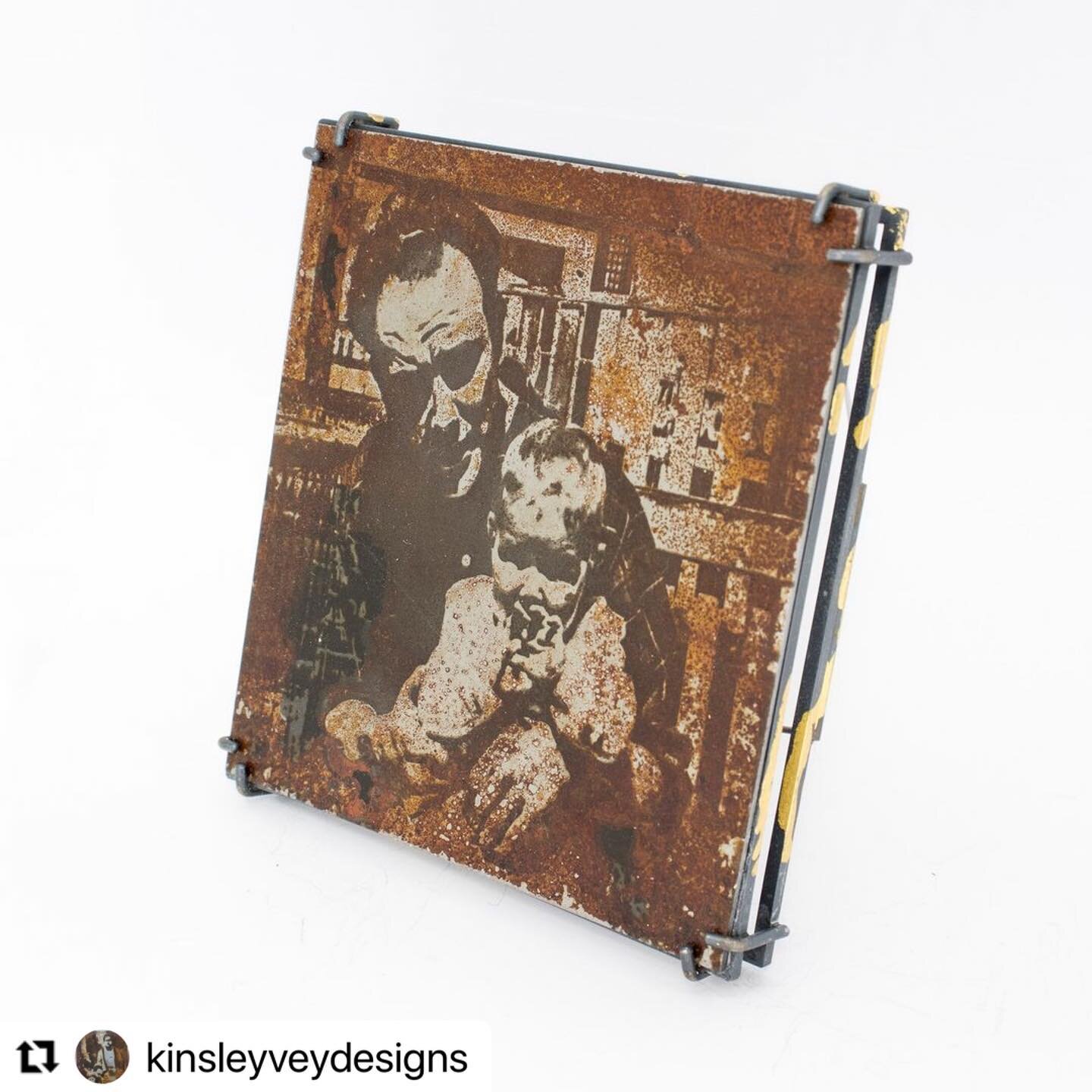

Christian Demmings

Spray and Pray

Basswood, brass, acrylic paint

NSCAD professor Kye Yeon Son’s brooches show us the potential of a simple piece of cut wire. Her studies in form have been built, element by element. She works dynamically and intuitively as only a master can. This methodology of mastering a singular material or technique is echoed in the work of Chantel Gushue, Erin Christensen, Berkeley Brown, Sarah Sears and Carolyn Young. Youngs’ Curled Pod Brooch 1 is an elegant conversation between a laminated and twisted slip of wood and rigid stainless steel. Brown’s Kinetic Brooch elevates the humble rivet to a clever, wearable system that evokes a steampunk interpretation of lace. Sears restricted herself to a patinated alloy to create a striking wearable monolith while Gushue, in Orthorhombic A and B applies scoring and bending (an integral silver-smithing technique) to wood. The scale and profile are suggestive of an obstacle or burden, however a surprising lightness alludes to the artists’ analysis of a personal metaphor. These deceptively light, hollow bodies become more like vessels for thoughts of self-doubt and false perceptions.

The jewellers currently practicing in Canada have been leading the way in re-examining processes weighted heavily in tradition. Erin Christensen’s work would be a delight to any metals traditionalist, as she employs the ageless tradition of chasing and repoussé almost exclusively in her work to create ethereal, rich, Baroque forms. Jessica Van De Brand adds a welcome Gothic voice to the current dialogue in cloisonné enamel, while Mengnan Qu pushes away from formal enamelling to offer experimental techniques in traditional Chinese lacquer and mother-of-pearl, in order to discuss the recent One-Child Policy in China.

Kim Paquet

Side Effects

Steel, sapphire, silver, grout, paint, foam

The works in Broach I Brooch hint at the resurgence of the use of narrative in contemporary jewellery. Recent NBCCD graduate Christian Demmings’ work (beautifully featured in the promotional material for the exhibition), Spray and Pray, is a rich personal lexicon of imagery and text. Demmings successfully collages multiple materials and perspectives, leaving you wanting to know more about his dark dreamscape. Emily Wareham, Kate Ward, Dorothée Rosen and Robert K E Mitchell also use highly personal narratives. In contrast to the experimental Demmings, their work is representative of the austere refinement that comes with years of practice. Wareham effortlessly incorporates tulle mesh as a metaphor for the tethers of motherhood, while Mitchell’s Looking for Goldfish is a pictorial homage to memory and the passing of time. In contrast to the irreverent joy in works like that of the inimitable Meris Mosher, Zhan Zhan and Magali Thibault Gobeil, Mitchell’s textures are the result of years of deliberate and refined alchemy.

Meris Mosher

January 1990

Copper, cubic zirconia, enamel, lustre

Not only is it a credit to Co-Adorn that so many artists responded with considerable efforts for this call, but to see such diverse approaches like that of visionary emerging artists Kim Paquet

and Katia Martel, side-by-side with Janis Kerman and Paul Leathers, leaves one with great optimism for the future of contemporary craft in Canada. The high-traffic area of Craig Gallery at Alderney Landing is the perfect location to spread the word, as even the most skeptical among us would be humbled by the endless hours of expert craftsmanship represented here.

Banner image:

Berkeley Brown, Kinetic Brooch

Sterling silver, stainless steel