Drawn to Water – Conversations with Robert K.E. Mitchell

By: Lindsay MacDonald

Published: 2020/07/14

The following is a summary of conversations held with Robert K.E. Mitchell from 2018 (during his solo exhibition, Flow at JJ Studio) to July 2020, upon his election to Chair of the Material Art & Design Department at OCAD University in Toronto, Ontario.

Robert K. E. Mitchell (centre) with JJ Studio and Gallery owners Alice Yujing Yan and Jay Joo at Flow exhibition

Photo by Brian H Wade

Mitchell is no stranger to the bombastic world of emerging artists. His students are on the cutting edge of interdisciplinary experimental discourse in Material Art and Design at OCAD University in Toronto. With this hub of activity at his fingertips, Rob (as he’s known to his students) works with a refined deliberateness in his own practice, which comes from decades of dedication to the craft.

In his 2018 exhibition Flow at JJ Studio and Gallery in Toronto, Mitchell combined a retrospective catalogue with his newest work. The comprehensive selection appeared as evidence of his life thus far. It revealed his decades of dedication to varied disciplines: from painting to graphic design and ceramics, and finally to the field of jewellery which has captured his interest for

the past 25 years.

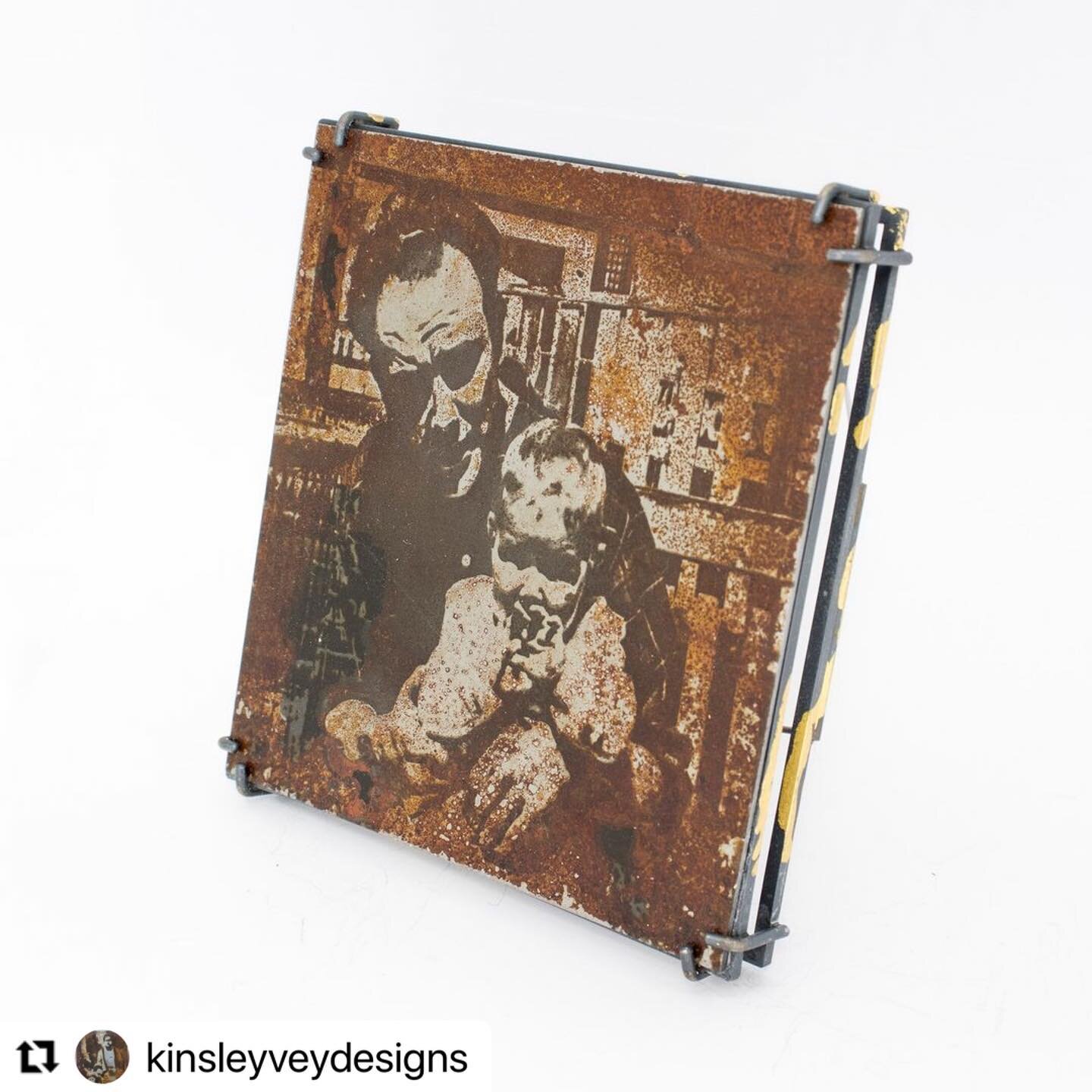

Robert K. E. Mitchell

Echoes from the Beach (2018)

14K Yellow Gold, Sterling Silver, Opal Doublet

4.5cm x 3.5cm x 0.5cm

Mitchell’s Flow began at Willow Beach, Ontario, with a tribute to a community of artists who used to gather under the umbrella of Jane McCaul until 2005. His series Willow Beach set the tone for the retrospective portion of the exhibition. It included gathered pebbles from the original site, a hand-cut map of heat-treated sterling silver sheet representing the topography, completed with a detachable diamond setting to mark the exact location of the annual gathering. Upon entering the exhibition, one is met with an auditory installation of the sound of trickling water meant to evoke the land wherein like-minded artists once gathered. This emphasis on community was felt throughout his retrospective. It was thematically present and reinforced by the fact that during the past 15 years, Mitchell has created work largely in response to calls for entry: each one a significant challenge; each one propelling him forward.

The quiet mastery of Flow was built like a shell beach with each fragment finely wrought, otherworldly, yet elemental. The poetry of water was reflected not only in the wearable forms but in his incorporation of raw materials: pebbles smoothed by current, baroque pearls, and cuttlefish bone. Mitchell revelled in traditional goldsmithing technique while adeptly encompassing moments of experimental methodology, which is the cornerstone of contemporary jewellery. Among the myriad materials he employs are moose hair, salmon bone, concrete, acrylic, pebbles, steel, and even a USB key. Throughout his career, these moments have shone bright.

For Flow, all of Mitchell’s surfaces were elemental and organic. Topographical micro worlds were integrated into pendants, brooches, and earrings. His skeletal fish motif was fused into many of these micro worlds, employed as a highly personal symbol of death and rebirth. Mitchell’s recollection of finding this fish during a trip to Venezuela was in sharp relief amongst a lexicon of personal symbology that ran throughout the exhibition.

Robert K. E. Mitchell

Flow exhibition

The Porcelain Beach

Photo by Brian H Wade

The attention to detail extended not only throughout the work, but into the installation space. Mitchell tells of altering his own display busts, sculpting and casting until they fulfilled his exact specifications. He consulted an MRI cross-section of a neck to create the forms to mount his necklaces. He carefully arranged his framed work by alternating heights mimicking a river’s flow. The finely tuned backdrop created the ease necessary to highlight the metaphor of chaos and control; a theme that could be detected at both the micro (natural casting techniques etched into surfaces) and macro levels (sculpted ceramic shells scattered along a constructed gallery edge). Mitchell used the metaphor of water to transform the space into a timeline and a poignant personal narrative about love, community and ecological urgency.

Robert K. E. Mitchell

West wall of Flow installation

Photo by Brian H Wade

Robert K. E. Mitchell

Evolution of Adornment Bracelet/ Transformation of Social Value Bracelet 2009

18K Yellow Gold, Canadian Diamonds, Sterling Silver, Mokume Gane, Cast Salmon Bone, Moose Hair, Cuttlefish Casting, Turitella, Beach Pebbles, Hand-carved Black Plexi, Bubble Cut Citrine, USB Flash Drive

3.0cm x 20.32cm

Photo: Robert K. E. Mitchell

His Coast to Coast bracelet was exhibited at the Cheongju International Craft Biennale in South Korea in 2009, and a second edition of the series, the Evolution of Adornment won Best in Show in Transformation, at Zilberschmuck Gallery in 2013. Just as in Evolution of Adornment, Mitchell has often applied investigative problem solving to handle disparate materials. He encourages his students to do the same. In his Jewellery Explorations class, each student creates an entire catalogue of material samples with corresponding technical data, culminating in a finished piece.

While the fast pace of creation that Mitchell teaches is exciting and dynamic, I would argue that the beating heart of his own work lies within its subtlety and the sublime beauty of each grain of sand; a distillation that is necessary to tell the quiet story of a footprint on a beach. His fingerprint is identifiable and so acutely his. In fact, some of these subtle treatments, notably his fusing of gold elements to silver, are of his own invention. They are the results of hundreds of hours of painstaking experimentation with bespoke metal alloys. His “caviar” (a nod to the history of luxury) are clusters of tiny, interlocking silver elements. Anyone who has endeavoured to control metal with heat would delight at Mitchell’s process of lining up dozens of third-arm tweezers, to torch multitudes of tiny wire fragments, knowing exactly how much heat to apply and when to pull away.

Mitchell approaches experimentation with the freedom of the artist and the diligence of a scientist. This methodology extends into his teaching for which he won the Price Award for Teaching Excellence in 2008. The Jewellery Explorations course was his conception, meant to introduce the world of materials through a jewellery lens, to any student enrolled in the overarching Design program. Not only was his intent to acknowledge the broadening scope of contemporary jewellery but also to encourage students to be critical of the traditional value structures surrounding adornment. He notes that once students are free from the daunting idea that they need to invest hundreds of dollars of silver and gold into their projects, they are better able to develop their own independent voice. Past students have explored concrete, vinyl, fruit peels, felt, and chewing gum, successfully elevating these humble materials to precious. Easier said than done. What these students might discover is that to make something out of “nothing” takes rigorous observation. The next Jewellery Explorations course is slated for September 2020. What better time is there to exercise the democratic approach of these material explorations?

In 2013, Mitchell was commissioned by the AGO to design and make a mount for the ivory sculpture, St. Sebastian by Jacobus Agresius (c.1638). Using the attention to detail and problem solving that characterize his work, Mitchell created an elegant metal armature disguised as sculpted loincloth to gently support the dynamic pose of St. Sebastien. I would suggest that this significant structural component acts as a metaphor for Mitchell’s career thus far, as an artist wholly invested in his community and a lifelong instructor. This is the way Mitchell has constructed his world. His art is holistic; he surrounds himself with it, he teaches it, he lives it, it’s endless.