Interview with Barbara Cohen

curator of Seeing Red exhibition, Craft Council of BC Gallery

Vancouver, BC

Conducted by: Amir Sheikhvand

Introduction by: Marie-Eve G. Castonguay

Published: 2017/08/27

Barbara Cohen’s artistic practice goes far beyond the walls of her studio. Textile and jewellery artist, curator and art jewellery advocate, she is an extremely active and dedicated member of the Canadian contemporary jewellery scene. You may have heard her name recently as she was the curator of Seeing Red, a contemporary jewellery exhibition that was presented this summer at the Craft Council of BC Gallery. She tells us about her practice as a jewellery artist and as a curator.

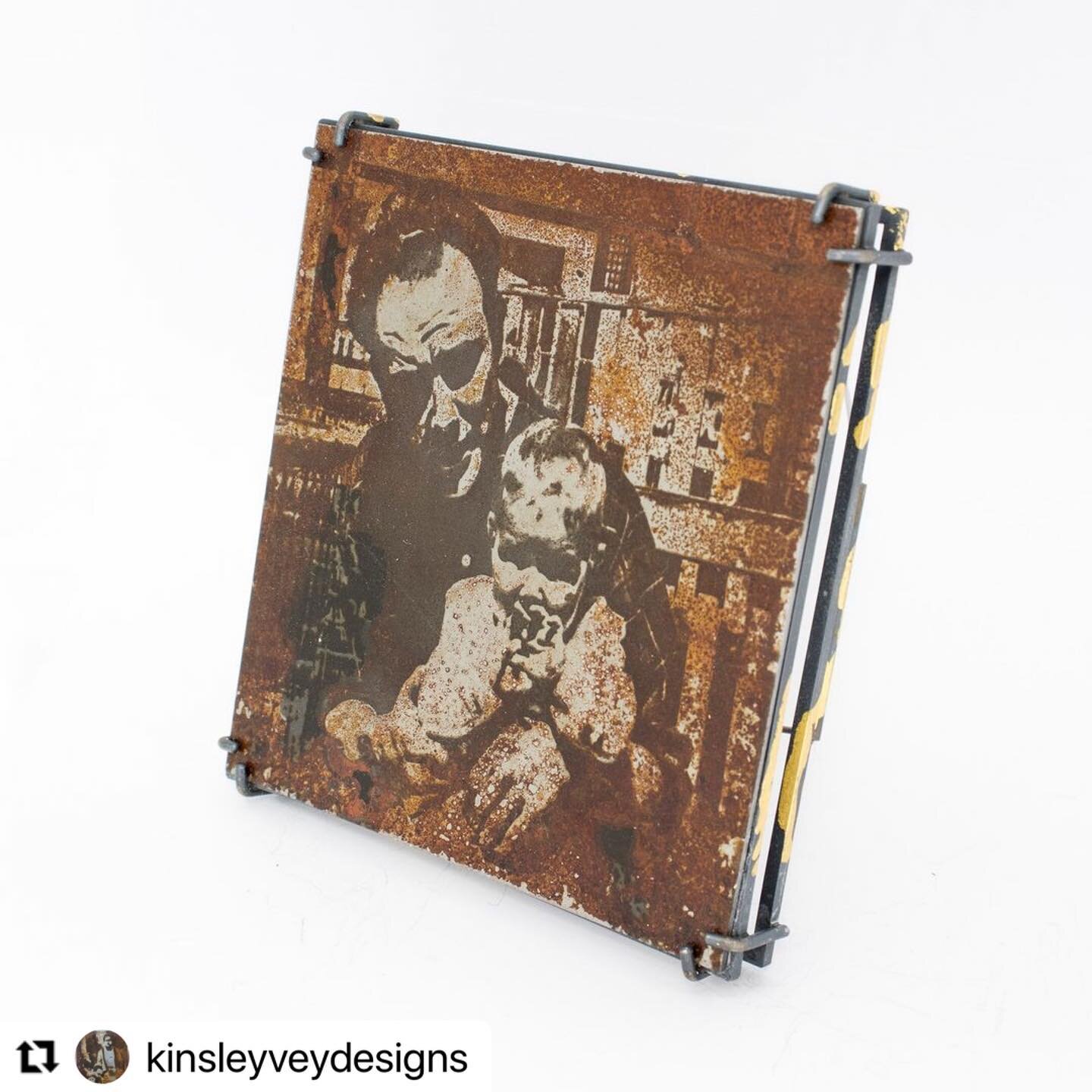

Amended Fracture

Gauze & handmade paper, paint, smokey quartz, wood, cord

Can you tell us about Seeing Red, your most recent curatorial project?

I was first invited to curate an exhibition by Circle Craft in Vancouver in 2013. Seeing Red, a national exhibition at the Craft Council of BC Gallery, was the fifth show that I have curated since 2014, with the goal of introducing and promoting contemporary art jewelry. My inspiration for Seeing Red came from an all-red Ela Bauer necklace that I purchased at Noël Guyomarc’h Gallery, in Montreal, in 2016. Ela’s piece is a joyful one to wear; it makes a very bold statement and brings many compliments and smiles to people’s faces when I wear it. For this exhibition, I asked each artist to feature the colour red in their pieces. My shows are by invitation, and many of the artists in this show have been in my previous exhibitions. But I always try and include some new people and emerging artists and Pamela Ritchie, Kye-Yeon Son and Noël were helpful in that area. As always, I favour more unusual approaches and materials. The 19 artists, including myself, were from across Canada and showcased an exciting and well-received collection of contemporary art jewelry.

How do you define Contemporary Art jewellery? Or Art Jewellery?

Like any other art form, jewellery has continued to evolve and change and incorporate materials that have gone way beyond the more traditional precious materials of gold, silver, gems etc. and techniques that often do not include metalsmithing. The value of the materials has not always, but often, been replaced with the artistic value of exploring ideas, concepts and design and sometimes even challenging wearability. The works are often wearable sculptures that draw the viewer in and challenge preconceived notions of value. For contemporary art jewellery, it seems that there are no boundaries. The Vancouver art jewellery scene has been growing slowly, but certainly growing. That is due in part to the formation of the Vancouver Metal Arts Association in 2011 and the occasional workshops and exhibitions that have come about because of the organization and the exhibitions that I and others have been putting on. When attending openings, I always make sure to wear a different piece of jewellery to catch the interest of the gallery owner in an effort to further expand the awareness of art jewellery and reach a wider audience. And catch interest it does!

Turning Point

Gauze & handmade paper, paint, wood, sterling silver, amethyst, nylon cord

Celestial Blue

Oxidized sterling silver, wood, gauze & handmade paper, paint, resin

I would like to touch on your own practice. How and why did you decide to go into jewellery?

How and why did I decide to go into jewellery? My mother had very contemporary taste in art and jewellery and, as a result, I was always drawn to and wore unique jewellery. But, being the late bloomer that I am, it took quite a while to find my way as a jewellery designer. While attending Sheridan College, I majored in textiles and followed that practice for many years, preferring to work with softer materials. It was deciding to make a friend a necklace for her birthday in the late ’90’s that was the springboard for me to move towards jewellery making. I was very fortunate to have success early on with a stone and fossil collection that sold well in Seattle and encouraged me to continue.

But it was the small piece of mesh that I purchased in New York 15 years earlier as a textile artist that really moved my career as a jewellery artist forward. Many opportunities resulted from my mesh collection and I am grateful that it had the success it did.

What are the developmental phases in your making process?

I tend to be very analytical and live in my head a bit too much – I have worked as a play therapist and had my own counselling practice. So when it comes to my art – that is my time to play and get out of my head. With the exception of one conceptual body of work that I exhibited in 2011, I prefer to simply focus on the pleasure I get from materials. As orderly and neat as I like to be, my studio is often a mess with copious amounts of different materials lying around. And so, intuitively I sit and play, assembling and reassembling pieces, often working on several pieces at a time. Once a pleasing design is achieved, it is my engineering mind that then needs to engage to figure out how to construct the piece.

Do you have preferences in terms of materials or techniques?

I do enjoy recycling and using materials out of context and it is often the things I find and am drawn to that inspire my work. Narrowing down what I work with is a challenge for me, but lately, I have been focusing on wood, which was prompted by an invitational exhibition at Facere Gallery in Seattle. I was trying to use up some extra paper and gauze tubes that I had made as a textile artist. It was only when I slipped a piece of branch inside one that a collection began to emerge and that my use of wood became more prominent. I remember one artist mentioning that she enjoyed the physicality of painting and I didn’t quite understand what she meant. But as I sawed, hammered and split wood for the Seeing Red exhibition, I understood.

Balancing Blue

Gauze & handmade paper, paint, oxidized sterling silver

Layers

Wood, paper, paint, glass beads, steel, zipper

Do you believe that every young jeweller needs to learn traditional techniques?

A friend and I joke that in our next lives we’ll come back and seriously study metalsmithing. There are many successful art jewellers who do not employ any metal techniques, so I do not think it is essential, but still I believe that it is an excellent background to have. I do regret that I don’t enjoy working with metal and that my skills in that area are fairly basic. Therefore, I do need to rely at times on someone else to fabricate certain parts of pieces for me. Moving forward, I am trying to incorporate less and less metal in my work.

How important is wearability in your jewellery?

I love wearing contemporary jewellery so, for me, it’s very important when I’m designing a piece or deciding to purchase one. Between people seeing pieces in my exhibitions versus work on my body, there is often a different and more favourable reaction when it is worn. Context is much more important than many people realize. With my interest and effort in promoting art jewellery, wearability is a vital component for me.

Is it important that the viewer understands what you want to convey?

As I mentioned, the focus of my work is about the materials rather than trying to send a message. If there is any message I would like to give, it is how important art and design is in our lives whether we’re aware of it or not, and I see the jewellery that I and others make as an extension of that idea. Many conversations with people have been initiated because of the ‘portable sculptures’ that I wear. This in turn often gives me the opportunity to talk about and promote art jewellery. My mailing list is ever increasing as a result! But as a curator, I do know that my appreciation of some of the work submitted is often increased when I read the artist’s intent and information about a particular piece. The one that has the most prominence for me is Anna Lindsay MacDonald’s Dazzle ring series that taught me about the use of dazzle camouflage design on ships during the World Wars that helped save many allied ships from being sunk. A very important and obvious way that art actually saved lives. I was recently waiting in a long line-up and began talking with the young person in front of me who was reading a book on the World Wars. I was delighted to be able to tell her something about which I was quite sure she didn’t know and then I invited her to the Seeing Red exhibition.