The Maker’s Mark

curated by clarissa long

Burrard Arts FOUNDATION, VANCOUVER, BC

November 10 – december 17, 2022

By: Louise Perrone

Published: 2022/11/14

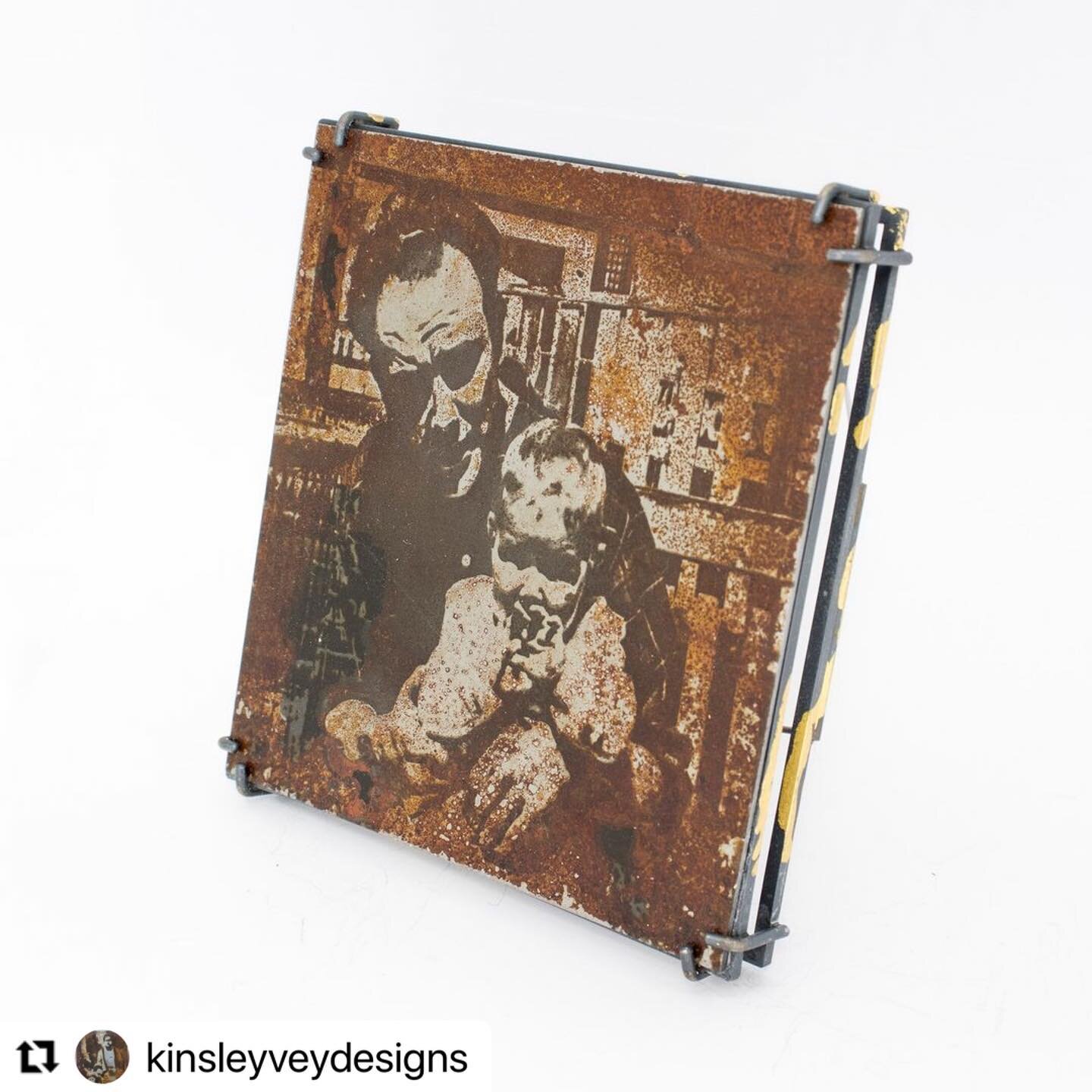

Detail of work by Jan Smith

Image credit: Ingrid Valou

How many times have you visited an art jewellery exhibition and been bombarded with a plethora of objects from multiple, disparate artists, crammed into a very small venue? You leave overwhelmed, having overlooked several pieces that weren’t given the space they needed to breathe. For anyone outside of the art jewellery world, visiting an exhibition like this, which, in their eyes looks not dissimilar to a pop-up shop, only confirms their misconceptions that jewellery does not carry the same gravitas or value as fine art.

The Maker's Mark at Burrard Arts Foundation (BAF) is the antidote that I have been waiting to see in Vancouver. The problem of low visibility for art jewellery in this city, caused in part by limited spaces to exhibit fine craft, combined with the absence of a degree-granting jewellery program to foster educational dialogue around jewellery, has been one of the issues the Vancouver Metal Arts Association has sought to address since its inception in 2012. This exhibition is their latest output, and the enthusiastic audience response at the opening reception was a tribute to how far the Vancouver art jewellery scene has come.

The Burrard Arts Foundation is a large gallery space with high ceilings; a perfect white cube with excellent lighting for large-scale sculpture, painting, and installation. I've seen jewellery exhibitions in spaces a fraction of this size feature over 50 different artists, but for this show, curators Clarissa Long of the VMAA and Andrea Valentine of BAF selected just seven jewellers. Ranging from emerging to internationally recognized, their approach to jewellery making is informed by different technical backgrounds, including traditional goldsmithing, art school, trade school, and self-taught. The pieces in the exhibition survey the wide range of techniques and materials currently used in contemporary jewellery, including precious metals and gems, enamel, found objects, waste plastic, fur, wood, textiles and paper. What unites the work is a depth of meaning behind each piece. This exhibition goes far beyond jewellery as ornament. Each artists' work is given its own space in the gallery, either hanging on the wall or placed on plinths. In the centre, one large plinth displays a single ring from each artist, in conversation with each other like figures in an architect's model. There are no labels on display (a printed guide was available at the entrance), and in between each body of work, the walls are empty. I noticed visitors at the opening reception were gathering around the exhibits and leaning in, taking a long time to engage with each piece, perhaps because they were given the visual cues that this is Art, look closely, think about what you are looking at; what does it mean to you?

Morgan Asoyuf’s installation

Image credit: Ingrid Valou

Morgan Asoyuf with her work

Image credit: Ingrid Valou

The largest wall in the gallery was given to the work of Morgan Asoyuf, an indigenous Ts’msyen Eagle Clan artist from Ksyeen River (Prince Rupert area), BC. Asoyuf has the most extensive training in traditional goldsmithing of all the artists featured in the exhibition. This, combined with her deep connection to her ancestral and contemporary Indigenous culture and visual language, makes her work stand out as the heart of The Maker's Mark. Three beautifully crafted necklaces hang on the wall between two large photographs of Indigenous activists adorned with regalia that Asoyuf has made to honour and protect them. After years of Indigenous jewellers being overlooked in contemporary jewellery exhibitions and publications, I was excited to see this important work being given the space and respect it richly deserves.

Respect and concern for the environment was a theme that echoed throughout the show. Bridget Catchpole, Jan Smith, and Jesse Gray all live and work in small coastal island communities that have been undeniably affected by climate change. It was interesting to see their different approaches to addressing this enormous problem exhibited adjacent to each other. Jan Smith of Salt Spring Island’s most recent work is quiet and meditative, drawing the viewer in and asking them to reflect on these beautiful, fleeting, endangered moments in nature. Jessie Gray’s rings are an intimate investigation into the unique qualities of the ocean-ravaged plastic objects that she collects from the beach in Nanaimo and casts in bronze. Gray’s art practice explores waste accumulation, examining the underlying history of human-made, fragmented found objects that she collects and reworks.

Jan Smith [left] and Bridget Catchpole [middle] at the opening reception next to Catchpole’s work

Image credit: Ingrid Valou

In contrast, Bridget Catchpole’s enormous sculpture made from plastic waste hangs in the middle of one of the large Gallery walls, dominating the space. Catchpole has created custom-made hooks to hang the work, crafted from driftwood that she found on her local Hornby Island beach. Despite its monumental size, this work has not travelled far from its origins as jewellery; an enormous toggle clasp rests securely in a Y-shaped branch that protrudes seamlessly from the wall, and on the other end of the chain a huge jump ring fits perfectly over the corresponding stump, satisfying my jeweller’s eye immensely. Catchpole has been working with post consumer plastic since 2004, and as she said at the opening reception, ”the problem with plastic waste isn’t getting any smaller, and neither is my work”.

The work of Carmel Boerner, Yoshie Hattori, and Jaime Kroeger speaks to a deep connection to material and process. Boerner's earlier works on display utilize decaying rusty nails and tools, celebrating their visual and physical weight and beautiful patina. Her latest work has a sense of refinement, the antique faceted nail heads that she has set into a neckpiece become human-made gems that bear their own makers' marks and speak to the nobility of skilled labour and the strength and value of materials that are made to weather the test of time.

Carmel Boerner with her work

Image credit: Ingrid Valou

Detail of work by Yoshie Hattori

Image credit: Ingrid Valou

Yoshie Hattori’s delight in the process of making is evident in her eclectic choice of materials and anti-hierarchical approach to construction, utilizing skilled wrapping and hand-stitching techniques alongside mechanical staples. Her choice of contrasting organic and industrial materials play on the idea of creating meaning and value through skilled labour.

Jamie Kroeger’s vision for her work in this exhibition was for it to be displayed low to the ground, as if the pieces had been dropped or fallen out of a hiker’s backpack. Through materials, process and concept Kroeger is translating the relationship between people and outside environments, and the viewer is drawn in to the story, bending down to examine the details and make connections.

Curators take note: less is more. Art jewellery deserves and needs the space to breathe. The Maker’s Mark exhibition has made its mark on the Vancouver art scene by allowing the work to speak for itself, and people are leaning in and starting to listen.

Banner image: work by Carmel Boerner, photo by Ingrid Valou