Sunday Funnies

Mary E. Black GALLERY, halifax, NS

july 11 – august 25, 2024

Review By: Lindsay MacDonald

Published: 2024/08/15

Sunday Funnies at Mary E. Black Gallery

Don't forget your I.D! It's not often a jewellery exhibition gets a rating of PG-13; Nick Rosin's Sunday Funnies, currently on display at the Mary E. Black Gallery, is bravely irreverent and bound to surprise one or two passers-by of the gallery's popular waterfront location. For that reason, the gallery has issued a gentle warning in regards to "mature content referencing drugs, alcohol, and sexuality". Rosin has exquisitely fabricated artifacts of day-to-day life, from cigarette packets to fast food wrappers, and emblazoned them with comic-style scenes of modern-day revelry. From tea and pie to bodily functions and recreational drug use, in Rosin's world, nothing is sacred. Even a Sunday of worship is ripe for his debaucherous graffiti. Hand crafted vessels refer to artifacts of Christian religious services. If you have attended a Christian service, you might recognise a chalice, a church window, vestments and even the sacrament itself, each emblazoned with Rosin's mischievous (and expert) hand engraving.

Nick Rosin, Gulp of Glory, brass, sterling silver, automotive lacquer, cubic zirconia

Having been painstakingly applied to metal, in Rosin's hands, the typically fast expression of graffiti is given a gravitas befitting of an artifact in any museum collection. He shared the fact that he drew inspiration from a Medieval chalice from Germany that he discovered at the Metropolitan Museum, on which the engravings depict the humble goings-on of saintly looking figures. Looking at this item, I can clearly see why Rosin would have the urge to add something more indulgent to the lives of these stoic figures. Cell phones figure prominently in his work, wielded amongst the scattered debris we might recall from our collective trauma of COVID isolation. Rosins' figures are indulging in everything and anything. And who can blame them? Eve and the Virgin Mary are each depicted on a tablet holding Cell phones (Stories on a Tablet). However, aside from these two selfie loving influencers there is no female representation among the revellers. In a craft that so long ignored its female makers, it's fair to wonder when and where our bacchanalian will be.

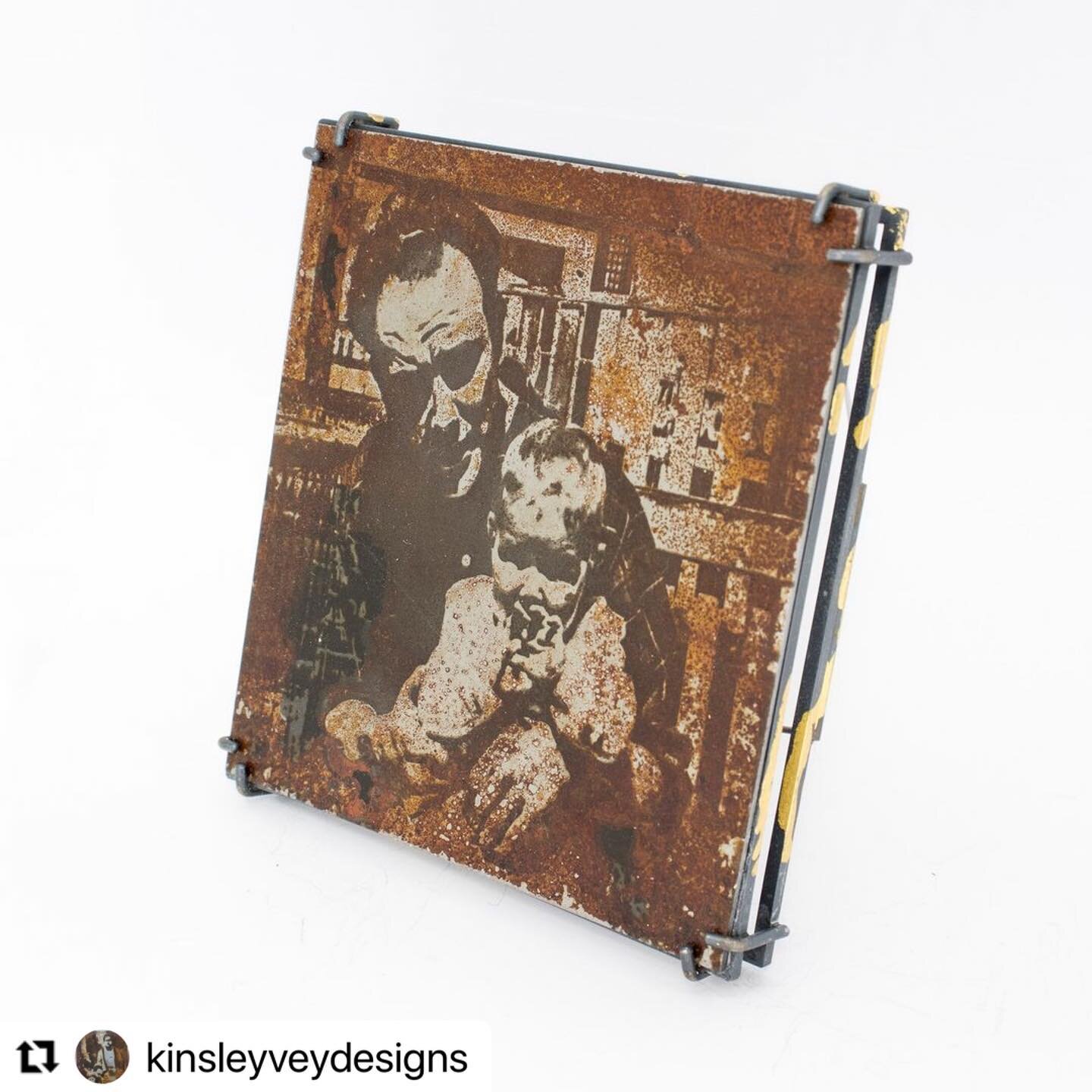

Nick Rosin

Stiff Whiff

brass, automotive lacquer, cubic zirconia, hematite, garnet

Rosin is vague about his current affiliation (if any) with a church and only uses religious iconography as an entry point to grab attention and encourage a viewer to assess what it is they might do to "blow off steam". He asks us why we can't apply a sense of reverence to these restorative acts. I do wonder if Rosin is worried about offending viewers. A visitor who places great importance on religious iconography might raise some concerns. But then I remember that these narratives are the embodiment of Rosin's wandering mind during church services in his younger days, thinking of happier and funnier times– and who can argue with that? By all appearances, Rosin seems comfortable in presenting this work. He disassembles the toxic old adage of art making: '[if] you aren't uncomfortable; are you in fact doing anything?'. Once you painstakingly carve an image into metal it's difficult to retract, so in that way Rosin seems very comfortable and he IS doing. A lot. One could argue that for Rosin, the content is not where the risk lies. The risk instead lies in how he's going to flush set a stone in a curved surface or execute so many extensive solder seams in one object. That's where we are invited to join Nick Rosin in his journey.

The Mary E. Black Gallery which is run by Craft Nova Scotia is mandated for exhibiting Fine Craft. From their dynamic Summer Artists-in-Residence exhibition to their thoughtfully selected yearly programming, they are no strangers to hosting work that pushes boundaries, and yet it was exciting to see how fearlessly they collaborated with Rosin to display Sunday Funnies. Chalkboard panels in the shape of church windows line the walls, each one scrawled with Rosin's delightfully debauched comics. A beautifully fabricated and (possibly functional) bong is featured prominently amongst the objects, holding the opening night flowers. Fabricated condom wrappers are skittered across plinths in a devil-may-care array alongside an empty and unmarked (fabricated) pill container. Each plinth is covered with a swathe of Astroturf suggesting some bizzaro-world sense of status quo. Everything is done perfectly and exquisitely, save for one piece called Love thy Selfie which stands out due to its deceptive simplicity. In it, Rosin replicates the size and proportions of a tablet cell phone and intuitively draws a simple heart in red lacquer. The simplicity adds a little breath in a room full of meticulous detail. Lacquer painting is noted for being painstaking and time-consuming work, and so it is with perfect tension that Rosin applies the quick sketch of a heart with this medium. The message seems heartfelt and like a parting wish to not take things so seriously.

Nick Rosin

Love Thy Selfie

sterling silver, brass, lacquer, cubic zirconia

Nick Rosin

Communion Chalice

brass, sterling silver, automotive lacquer, cubic zirconia

Rosin is quick to humbly suggest that his messages are just musings from a bored, young mind. What I see is instead a mastery of tension from the fast/slow dual pace of his work to the sacred/sacrilegious messaging. The jovial tone of the work belies the 100's, (1,000's?) of hours Rosin has spent making the body of work thus far. You can feel the commitment in the continuity of his style, and the intensity of the craftsmanship. There is no backing down from either a scandalous tableau or a terrifying stone setting.

It seems very likely that these objects will live on past our lifetimes, taking their rightful place among other culturally significant objects in a museum collection. Future viewers will wonder what the artist was thinking and how the work was received– and if I read the room correctly at the Mary E. Black Gallery– we (the Craft audience) condone every transgression in exchange for the opportunity to experience parallel joy in Rosin’s technical accomplishments.

Nick Rosin

Stories on a Tablet

brass, plexiglass

All photos are courtesy of Nick Rosin except for those in situ which are by the author.